The National Security and Investment Act 2021 (NSIA) introduces a new statutory regime to provide for government oversight and intervention where UK transactions may impact on national security.

In this article we consider how this new legislation is likely to affect banking and finance transactions when it comes into force later this year (including its impact on historic transactions) and the risks for banks and lenders to consider when entering into transactions which fall within the scope of the NSIA.

What is the NSIA?

On 29 April 2021 the NSIA received Royal Assent. Its purpose is to establish a framework allowing for government scrutiny of certain investments and transactions, with the protection of national security being at its heart.

Although the government’s main priority is to control foreign investment in the UK where it could negatively impact on national security, NSIA will apply to UK and foreign investments equally. It proposes to do this via government intervention though a new statutory regime for notifying and obtaining clearance for transactions which fall within the scope of NSIA, which will sit separately to the existing competition regime regulated by the Competition and Markets Authority.

Although the regime is not set to come into force until towards the end of 2021, there are retrospective call-in powers which will reach back to 12 November 2020. This allows the Secretary of State to review transactions entered into after that date which raise national security issues and potentially unwind them in serious cases. As such, NSIA issues should be considered for all transactions completed after 12 November 2020. Once fully in force any transaction covered by one of the seventeen NSIA sectors will be void if it is not notified and cleared under the mandatory NSIA regime.

Call in powers are not expected to affect many transactions, but in some cases it may be advisable to seek informal guidance under NSIA for transactions completing between 12 November 2020 and when NSIA is fully in force. Once fully in force it is anticipated that mandatory NSIA notification will be relevant to around one third of deals and as such it is important that banks and other lenders understand the implications when entering into transactions which may fall within its scope.

Which transactions will be caught?

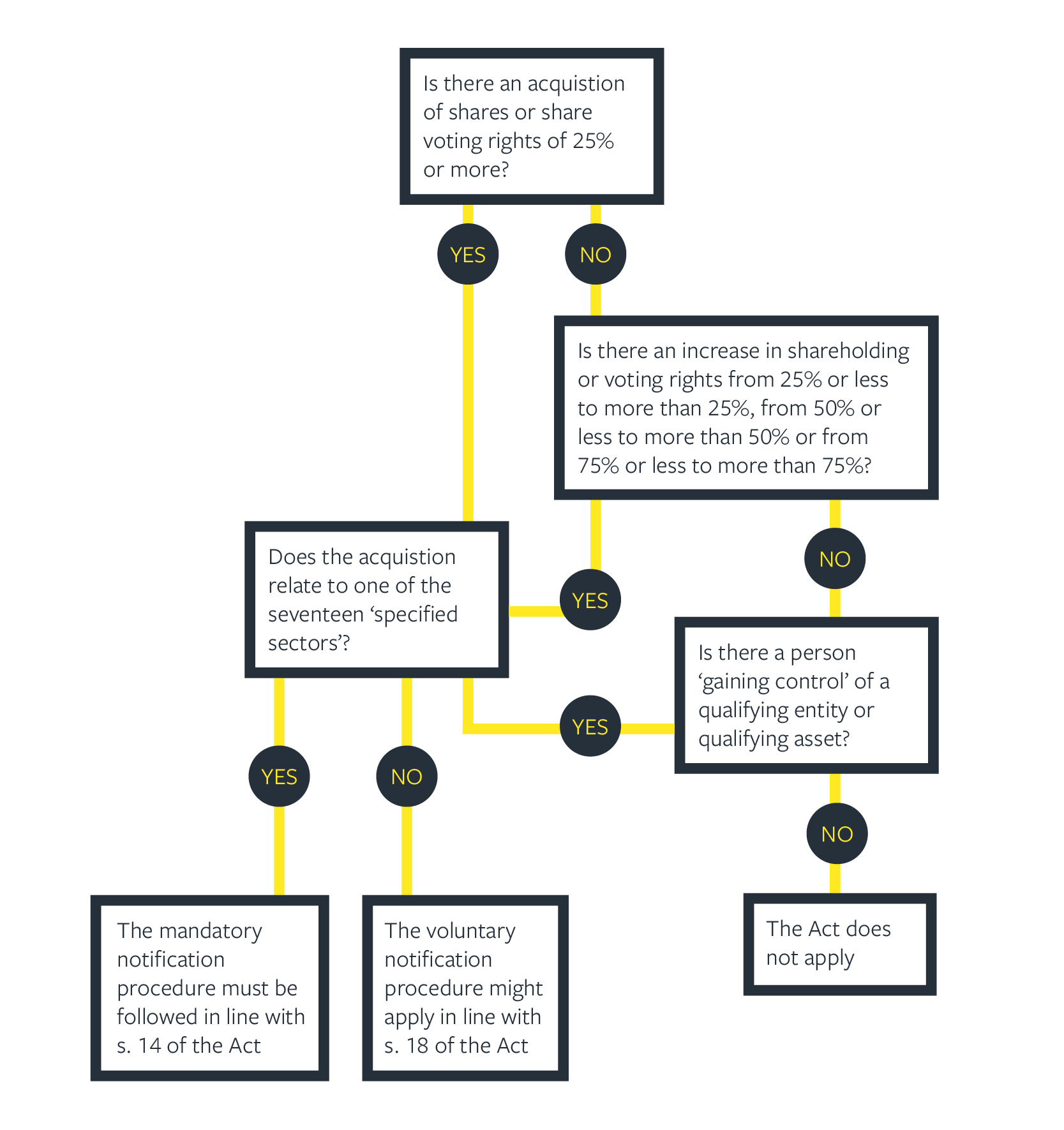

The diagram below sets out a simplified flow chart to consider the likelihood of a transaction being caught by NSIA once it is fully in force.

There is also provision in NSIA for the acquisition of specific assets or types of assets to be effectively brought within the mandatory notification regime, though the detail of this will be in regulations yet to be published.

Mandatory v voluntary notification

Mandatory notification is, as its name suggests, non-negotiable and failure to notify in these circumstances will result in the transaction being void and could result in the more serious consequences of fines and criminal convictions. Voluntary notification outside of the seventeen NSIA sectors or outside of specified assets being acquired leaves it up to the parties to decide whether to notify or not As noted, the NSIA’s call in provisions give the Secretary of State the power to review a transaction entered into after 12 November 2020 up to six months after being notified of the trigger event, or up to five years after the trigger event occurs if no notification took place.

NSIA therefore has the potential to impact a wide range of lending transactions, not necessarily limited to real estate or acquisition finance. It is therefore imperative that parties carry out full due diligence on all transactions, with specific reference to NSIA, and seek clearance or informal guidance where appropriate.

It should however also be noted that the situation may change over time such that NSIA may become relevant later. For example, changes in the business of a borrower or to the tenant of a property or to the use of neighbouring land may result in NSIA becoming relevant when it wasn’t at the outset of the transaction. As such, NSIA is a factor that lenders also need to consider as part of their ongoing assessments of the risks associated with a specific borrower.

Practicalities

With that in mind, it is important to think about how long the process of approval will take and the likelihood that approval will be granted. Currently informal guidance is taking about 30 days for a response. Once in force mandatory notifications have an initial timescale of 30 days for a response, but this is extendable if more detailed investigation is required.

The Secretary of State is required to decide whether to accept or reject voluntary notice under the voluntary notification procedure for transactions outside the seventeen NSIA sectors ‘as soon as reasonably practical’ and, if the notice is to be accepted, within 30 working days from the date of notification. If accepted then the same timescales as for a mandatory notification would then apply.

Clearance will depend on the detail of the national security risks on a case by case basis. Nevertheless, it seems unlikely that the government will want to interfere and impose remedies in a large number of transactions and they are expected only do so where there is a genuine threat to national security and this is expected to be circa ten transactions a year. This risk should be particularly low for transactions involving only UK investors given that NSIA’s primary intention is to curtail foreign investment in the UK which could potentially result in compromised security.

Until we start to see how NSIA works in practice it is difficult to predict how laborious and far reaching its introduction is likely to be for lenders in practice. It has the potential to capture a significant number of transactions, and extensive due diligence with NSIA in mind will be key to highlighting those which should trigger mandatory notification or where informal guidance or voluntary notification may be appropriate. However, whilst NSIA has the potential to catch many transactions, a national security threat will obviously not arise in the vast majority of transactions. So whilst NSIA may impact on deal timetables, it seems unlikely that it will have notable impacts on the overall outcomes for lenders in most cases, with the greatest impacts most likely being the risk of a transaction subject to mandatory notification not being notified and being void as a result or the risk of delays at the point of enforcement.